Lithos, at Monster Truck Gallery, Temple Bar is an exhibition of work by John Pusateri (NZ), Jessica Harrison (UK) and Ben Moreau (USA). In three periods since 2008, the artists have been resident on The Black Church Print Studio’s International Lithography Residency Programme. Monster Truck Gallery’s ground level features nine large, barely coloured prints that are smartly presented without framing. The building’s enormous front window makes their details instantly apparent. The exhibition’s title derives from the Greek word meaning stone. This appeals to a traditionalist quality in the format. Common to the artists is the use of figuration to explicate humanist ideas.

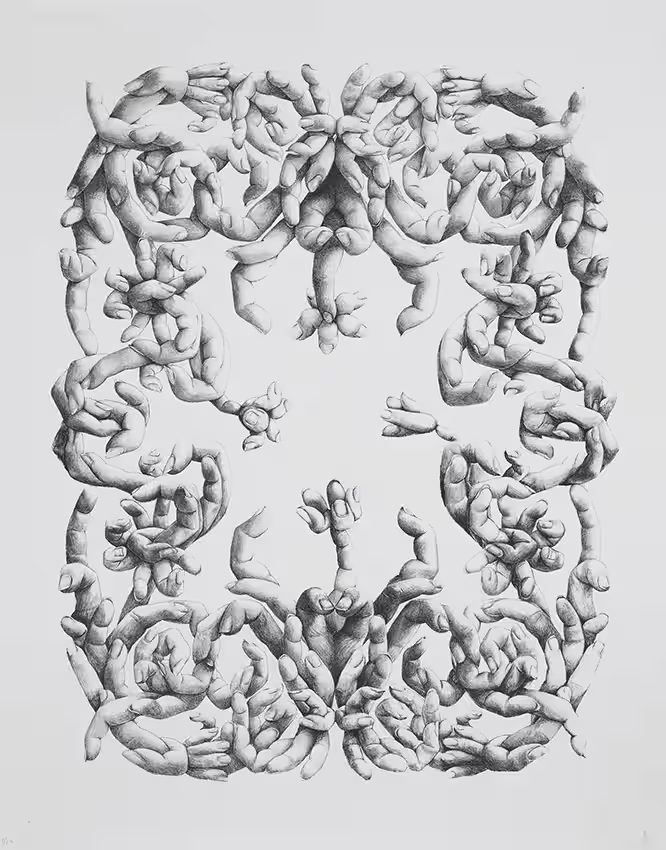

In Jessica Harrison’s series, she offers assortments of human forms made entirely from hands. Thrown portrays a maternal figure seated on an ornate throne holding a healthy looking baby, dressed in an ancient looking cloak that flows to the ground. Her body, where visible, is made from hundreds of interlocking hands that grip together to form a head, and flow down along the ground past her clothing; it takes a moment to realise that each hand has the correct number of fingers. In The Smoker, she depicts a cloaked figure caught in a halting motion, hands flailing into the air, moments after her head has exploded into an enormous puff of smoke. The work, completed on Harrison’s residency, arises from her occupation with xenotransplantation—the transfer of living body parts from one species to another. She uses this notion to provoke an emotive assessment of the dignity that wholeness grants. Her ideological focus on the singular self is robustly handled, omitting any venture into ethical judgment, while illustrating the tragedy and barbarism of personal invasion by biomorphic manipulation.

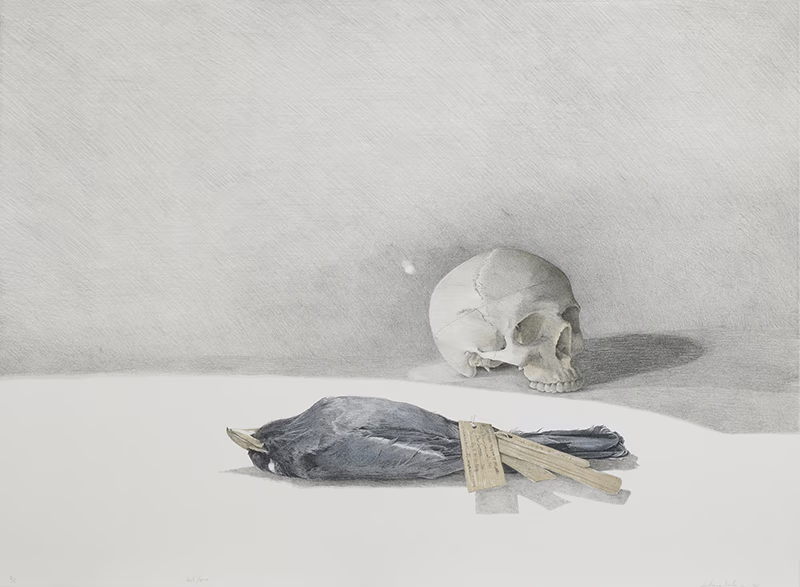

Each of John Pusateri’s lithographic works features a bare setting of a model human skull placed under or behind a brightly lit dead bird. While the composition may seem grim, his approach to the subject matter has a naturalist’s attitude. In Scale Figure II, the recreation of catalogue tags around a small bird’s leg is a memorably sensitive counter to Harrison’s bleak totality. He describes the background light in only incidental terms, focusing the wealth of his energies on an accurate reproduction of the study skin. Pusateri’s specimens are sourced from the ornithological collection in the National Museum of Ireland, mostly dating from the 1800s, which he was given free reign to photograph. He noted that each specimen had been given a number of tags throughout efforts to catalogue the collection, but the creatures rarely present enough information to constitute a scientifically valid study. That these tags are so prominently composed in the prints speaks to the attribution of fact to physically existing bodies — be they living or dead. The deployment of institutional predisposition is significant, considering the artist’s other projects undertaken in prisons throughout New Zealand. Aside from the subject matter, the technical skill evident at a close viewing of the work is effective, and made highly adaptable.

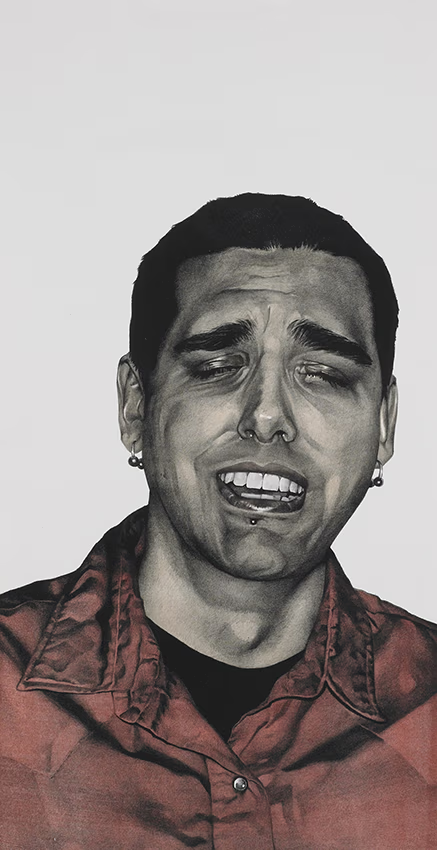

Ben Moreau’s three prints display his own head and torso with a recurrent pose. In each, the body is presented against a white background, off-centre and positioned at the end of the page. In I don’t seem able to depart (such is life), the subject contorts his face into an uncomfortable mock-scream; his expression, especially around the mouth, is intended to leave the viewer confused and uneasy. Rummaging into a self-imposed awkwardness is Moreau’s method of confrontation with the audience. He uses himself to catalyse perceptual anxiety—the sort of feelings of outward distrust that might accompany being lost in a large shop as a small child. His use of colour has an effect that recalls pop styling, but his lithographic method could be traced closer to an animated type of realism.

The exhibition extends to the second floor of the gallery in a section featuring digital work. This includes two works by Pusateri, A4 photographic studies expanding on his lithographic compositions. Ben Moreau’s single photograph captures ten exposures of his wife crying. The projected film, Flylashes, by Jessica Harrison made the most lasting impression. It shows a human eye, presumably hers, looking away from the camera and attempting to blink with a series of thick dark extensions attached to its eyelashes. As suggested by the title, she bought maggots from a fishing shop, raised them into flies, waited until their death, and cut their legs off to craft eyelash extensions. Oddly, this extreme endeavour into organic attachment is at its most disconcerting when the artist briefly glances straight into the camera.

There are a few sore spots; the ground floor addition of a digital slideshow featuring a demonstration of the lithographic process feels both incomplete and misplaced, and the quality of the photography is unequal to the aesthetic highs in the lithographic works. Lithos as a whole is coloured most by technical proficiency, ideological balance and a very fine aesthetic consistency; an unlikely result considering that the artists are brought together by residency. All three share Ben Moreau’s penchant for positional abnormality, while John Pusateri’s delicate management of humanoid and avian forms thoughtfully complements Jessica Harrison’s irrevocable construction of ethical hurdles and physical misdemeanours.