In the early 1980s Sun Myung Moon, leader of the Unification Church of Korea, poured $30m into one of the worst box-office disasters in history. The 1982 film Inchon dramatises the 1950 American invasion of Korea. Laurence Olivier delivered a weak performance as Douglas MacArthur; it was probably the worst of his career. Olivier struggled alongside a stuttering cast, cardboard set pieces and financiers who could barely conceal their religious zealotry. Newsweek memorably described the film as “a turkey the size of Godzilla”. It is from this sorry corner of cinematic history that Adrià Julià constructed his exhibition ‘Notes on the Missing Oh’.

The main Project Arts Centre gallery contained three films, which Julià projected on to sparse wooden screens. The largest, entitled Notes on the Missing Oh, was ten feet tall and fourteen feet wide, and obstructed the room’s front entrance. I wrongly presumed that I had arrived at the halfway point, a fixed monochromatic shot of a field and a dirt road. There was a tree in the foreground, just at the road’s curvature, and its leaves blew against a low rushing sound that issued from speakers near the ceiling. The image was very still, and quite transfixing. Most of its movement came from small pockmarks of 16-millimetre film grain, and the camera shaking in the artist’s hand. Eventually the scene trailed off into a light grey, it flickered for a couple of seconds, and transposed its way to the exterior of a small petrol station, under a clear grey sky. It stayed there for three more minutes.

In Notes on the Missing Oh, Adrià Julià focuses on a muted kind of space. Although he depicts normal movements – cars driving around, people walking or fishing – everything is slow, his subjects take their time. The viewer passes through city scenes, harbours, a fairground, and a series of subways. There were no particularly surprising recordings, and nobody in them was doing much of anything. In one scene, the artist positioned himself high above a roundabout, and captured a stream of ant-sized cars travelling around some indistinguishable concrete monument. Elsewhere, he captured a long panoramic view of the lake surrounding a long bridge. Here the camera jumped and stammered rightwards, passing the small silhouette of a fisherman at the water’s edge, and eventually turning a full circle. When the bridge flickered into grey, it was replaced by a fixed monochromatic shot of a field and a dirt road. There was a tree in the foreground.

How is it possible to resolve the meaning of these mute and indeterminate spaces, when Julià implicates a film like Inchon so heavily in the exhibition’s subject matter? Each of the film’s scenes was long enough to defuse any perception of what had already transpired; the artist prevented the viewer from juxtaposing his shots into a recognisable narrative. His material was so spaced apart that its meaning could only become more indeterminate as Notes on the Missing Oh went on. Julià coupled this muddiness with the fact that the film had no clear beginning or end. Instead, the viewer circumnavigated it, and in this navigation of unknowns lay the kind of perspective that is offered by a certain type of historical stock footage, which makes a time and place that has long passed seem once again apparent, populated and real. In place of what Inchon professed to understand about the Korean War, Julià’s scenes refused to know. Moreover, where Inchon made its subject matter into a direct, easily resolved trope, Adrià Julià allowed Notes on the Missing Oh to get lost in the drizzly complication of ‘real’.

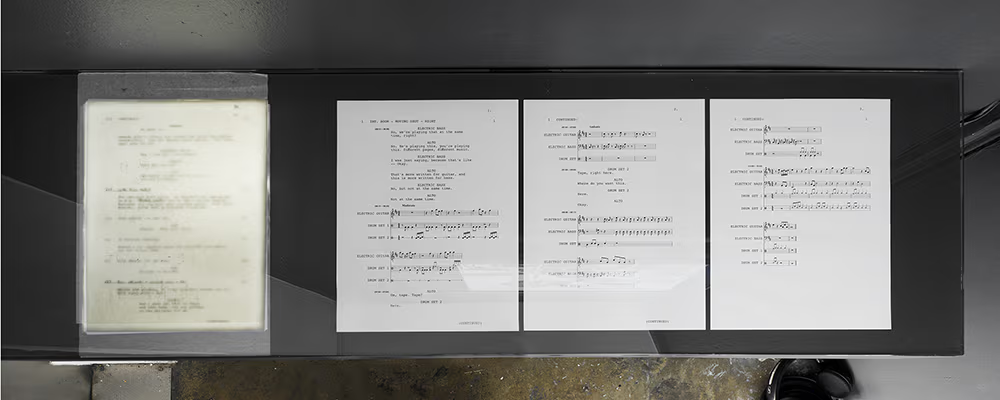

On the other side of the gallery, two mid-sized wooden screens closed off the room’s north corner. On the right was a short silent shot of Namgung Won, a popular actor in Korea who starred in Inchon. On the left, there was an interview with Dick Millais, a film industry figure of some sort, whose company came to possess the orphaned internegative of the Inchon feature. The shot of Namgung Won is very much in the style of the larger Notes on the Missing Oh film; it is silent, grainy and shot to film, with no beginning or end. The actor was in his 60s, and made halting, jerky facial expressions. He sat there for about four minutes, looking as though he was listening to his fraternal projection, or just waiting for something. Dick Millais, for his part, presented very differently to Namgung Won. His interview was in full colour, with dialogue throughout, and digital compression artefacts fracturing the space around his head. Millais told the story of how the creators of Inchon came to abandon ownership of their film. He comfortably brought up work colleagues and technical terms. He also called the artist “Andrea”. His recollections provided a counterpoint to the abstracted contextual information that Julià wove throughout the rest of the exhibition. In this interview, the artist seemed as much willing to allow the viewer a basic access point to his research, as he was to retool and manipulate the thin substance of Inchon’s history. The films featuring Dick Millais and Namgung Won are not synchronised, and yet it is hard not to imagine that Namgung Won is an editorialising figure – looking over at his fraternal interviewee – not really knowing what to say.

In making Inchon, the Moonies toyed with applying an overarching moral lesson to the Korean War. Adrià Julià has rewritten the film’s contextual trajectory with a realist’s restraint. The topic of the exhibition is stirring, and I initially feared that the artist would relish in the colossal failure of Inchon. But he did not. Instead, Julià’s representations of South Korea seize something of value out of the Moonies’ tepid sludge. Julià assumed that the audience would understand the logical and moral problems of characterising war by a saintly cartoon of Douglas MacArthur. Instead, ‘Notes on the Missing Oh’ offered a version of South Korea – with its quietness, its pacing – that gave a sense that life there is ordinary. In the simple act of recording and recollecting, Adrià Julià explained the weakness of the war’s retelling, by characterising the kind of ‘real’ that was not retold.