In late July, Pallas Projects/Studios (PP/S) presented two solo exhibitions side by side: Helen Horgan’s The horse’s mouths, and Angela McDonagh’s Small ways of observing, multiple possibilities. This was the second last show in the PP/S summer programme, a schedule of five artist-initiated projects that had previously hosted an excellent exhibition by Fiona Reilly.

The new PP/S gallery constitutes two ground floor rooms of an old Georgian house; both are around twenty feet square, with worn timber floors and a ceiling edged with plaster mouldings. The room occupied by The horse’s mouths is bright, its two windows face out onto the street.

The horse’s mouths featured six large, brightly coloured sculptures, each made with foam and wood. Five of the six works were electrically powered. Titles such as Hermes revisiting, Two-faced lyre and The boat Amphion make obvious reference to the gods and imageries of ancient Greece.

Walking into the room, I could hear the asynchronous clicks of two ticking devices. One of these, a carved foam face entitled The boat Amphion, swung from side to side in one-second intervals. The face, mounted to the wall, was about as large and thick as a car tyre. Horgan cut its eyes and nose into haggard tribal patterns, and pierced the back of its head with a light bulb that beamed up towards the ceiling. The face was fixed to part of a fire alarm, which created its noisy tick and wobble. This alarm was positioned below the face with its bell dislodged – it was powered by a car battery that sat on the floor beside it.

In a short text accompanying the exhibition, Horgan explained that Amphion was a name given to the pleasure craft of King Gustav III, and, despite its dubious seaworthiness, the schooner was used as a command vessel during the Russo-Swedish War. In this context, the wobbling ticking sculpture seems caustically witty.

The second ticking artwork stood in the corner of the room; a black wooden clock entitled Two-faced Lyre, a pendulum shaped like an oak leaf swung from its underside. Horgan ran a light bulb through the back of the clock, its wiring was wrapped up in insulation tape, and it shone yellow light through hundreds of holes drilled through the clock’s enclosure. Peering through a crack I could see a set of quickly rotating mechanisms. One cog had a black plastic bag tied to it. The bag was full with an unknown liquid, and it hung between the clock’s four legs.

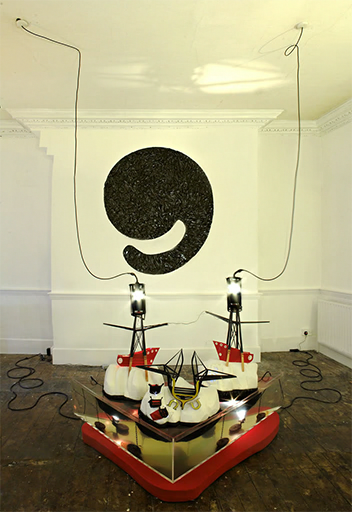

Mounted directly onto the wall of the gallery, overlooking the room was a meter-tall black apostrophe. It was wrapped in ruffled fabric that had solidified under a deep coat of black paint. The apostrophe’s tail looked as though a smirk had been carved into it. The apostrophe signifies possession, although illogically, it also connotes an omission. I asked myself how one could ‘have’ what is no longer there? I thought of the sunken Amphion.

The largest and most impressive work in the exhibit, entitled Hermes revisiting rested on the floor directly beneath The apostrophe, occupying a central portion of the gallery. Horgan had formed the work from a large triangular tank, made from clear inch-thick Perspex. The tank – which sat on top of a foam base, dressed in bright red fabric, contained two mock pylons, and two red lightships beached on three foam icebergs. Icebergs, which had been formed as sheer, geometric shapes, and wrapped in black plastic below the waterline. The bottom of the tank was dotted with dumbbell weights, paradoxically mooring the icebergs. Neither of these red lightships had a floor and through their voids a bright electric light shone up from the deep.

The wooden pylons overlooking the boats were capped by incandescent light bulbs. The bulbs reached eye-level, their wires ran out from the pylons, and up into fixtures in the ceiling of the gallery. Horgan encased each bulb in a rotating tubular window, which gave the effect of a lighthouse. The wiring from the rotating windows ran between the pylons, over the water, and down onto the floor where it was nailed into superficially haphazard loops.

I spent some time puzzling over how to interpret the title: The horse’s mouths. Its accompanying text began by recalling “the discovery of two stones whose facing profiles mirrored each other in outline and form,” and was directly alluded to in another work titled Two wise horses. In the same text, Horgan mentioned Vasa, a Swedish warship that was too heavy above water, and sank, a mile into its inaugural journey. This sort of history aligns well with the spectre of Greek tragedy – a gift that is generous, but consumes its recipient.

Hermes was the Greek patron of boundaries, travellers and commerce. He gave Amphion a golden lyre, a godly instrument that allowed Amphion to build the walls of a city by playing music to the stones; these glided into place at the lyre’s sound. His more practical brother struggled along by hand. Later in life, Amphion’s wife insulted the gods, and she and their children were killed for it. Consequently, Amphion killed himself. Perhaps as a mimetic gesture, the artist journeyed across Europe in search of the histories of the vessels Vasa and Amphion, and saw their hubris for herself. The two were present on her icebergs as analogies to one another.

Hermes revisiting offered an encapsulating view of Helen Horgan’s style; her installation is profuse. It wears its colours and wiring on the outside, and is top-loaded with references to an idolatry that has long since passed.