In March of last year I went to my first television focus group, something I had assumed existed only on television itself. Sally O’Reilly scribbled and flipped through pages on a whiteboard as she explained her plans for a sitcom about the art world. This plot reappeared as The Last of the Red Wine (the prequel/sequel), an exhibition-as-sitcom that offered the genre itself as a compromised and highly particularised model of representation. The show’s title sequence played on a television in the gallery foyer. In it, an unidentified figure uses a packet of matches to light up parts of a nude woman’s body, revealing a sequence of titles written on her skin. O’Reilly gave a whispered narration to these shots, facetiously emphasising the year that each work was made. This sequence formed the only obvious list of works in the show, and it began a purposely convoluted relationship with mediation by over-clarifying the gag, in line with the traditions of network television.

The largest work in the gallery, The Jynx, belonged to Bedwyr Williams; it was the site of a caricatured accident. The scene itself presupposed a narrative where Williams ascends some precariously placed boxes and scaffolding to monograph a perched bird onto the wall. The exact cause of the scaffold’s collapse was not clear. Amidst the rubble I retrieved a short publication that recounted the calamitous incident. With ‘caps lock’ set firmly in the ‘on’ position, Williams leads the reader through a few minutes of a vindictive inner monologue, in which few are spared. The final page was cut short by his smashing descent to the concrete floor, where he vomits a kebab and dies. On the far side of the room, there was a set of six short films variously projected and televised on a set of steel workshop shelves. In Doug Fishbone’s two-minute pledge drive, It’s Not You, It’s Me – Promo, a greasy winking sleazebag asks what the greatest nation on earth is. According to him, it isn’t the US, the UK or even Costa Rica: ‘the greatest nation on earth is donation’. There was a coin box underneath the television, which vacuously promised to ‘give children hope’. The video ends with a white logo depicting a fish skeleton, and the presenter’s surname emblazoned below it.

Behind the television, Hayley Newman’s My Studio took the viewer on a projected tour of the artist’s workplace: a graveyard. Newman walks the camera around, mentioning that the other residents are mostly quiet and that she receives few visitors. A few minutes later, she enacts the same studio tour in her bed, wantonly disregarding her own tenuous grip on reality. The grip was loosened further in Kim Noble’s video It’s not the despair, Laura. I can take the despair. It’s the hope I can’t stand. ~ Brian Stimpson, Clockwise. Here, a small clay figurine tires of his days spent working at the office photocopier, and imagines life as a caped superhero. As the scene shifts to starry-eyed dreams, our figurine is fastened to a metal prong on the windshield of a double-decker bus, zooming along the latitudes of London city. Noble’s video is set against a majestic orchestral score, the sort that can sweepingly accompany a steely-jawed paragon far across the universe.

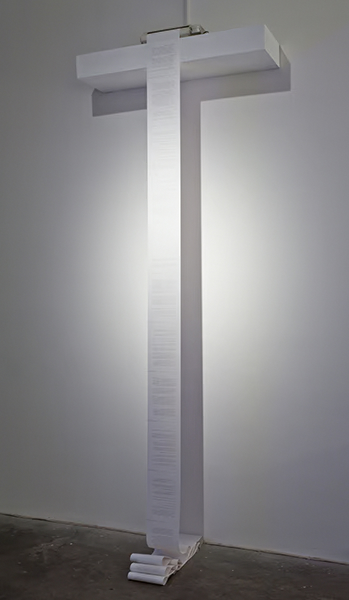

Every ten minutes Noble’s low orchestral motions were interrupted by a loud hiss from the ceiling, courtesy of a sound work entitled Last of the Red Wine Sound FX, which had no listed creator. It possibly constituted one of O’Reilly’s contributions to the show, which were entangled with her status as co-curator. This is the place where the Last of the Red Wine’ s relationship with mediation became simultaneously tricky and fascinating. O’Reilly was not only acting as curator here, but also included work in the show; for example, her collaboration with Marc Accensi on the match-lit title sequence, or in a video produced with Colin Perry comprising a 37-minute set of utterly ludicrous characterisations of artists taken from classic sitcoms. These were complete works, but they had an additional curatorial and contextual status that gave them a significant role in situating the show within the sitcom’s lexicon of visual culture. On the other hand, one of O’Reilly’s works had no curatorial status. She placed a fax machine on top of a high white shelf, to which she intermittently sent pages of her forthcoming book as they were written. A long ream of brightly lit thermoscript paper cascaded from the antiquated device down towards the concrete, where it pooled into a hill. It was possible to follow the narrative back upstream for a few pages.

In some places, O’Reilly is a curator working within The Last of the Red Wine, and her focus groups, scripts and clips mediate avenues of the show’s outsized personality. Elsewhere, she is the show’s primary protagonist, appearing in every scene and taking a production credit to boot. This state of irregular distraction is the most appropriate manifestation of a sitcom about art. The Last of the Red Wine devised complex arrangements of, and reactions to, this broadly accepted and useful genre of superficiality. And, it simulates some bizarre behaviour within that same comic mode of representation: everyone gets involved in the dreamy fun, but always while thinking about something else, and always while pretending to have better things to do.